Revisiting Shakespeare: “Measure for Measure”

For fans of Shakespeare and theater, get excited for the debut of “Revisiting Shakespeare.” Senior Managing Editor Edwyn Choi ’27 kicks off the column with “Measure for Measure,” one of the playwright’s darkest legal dramas, and unpacks the play’s entanglement with morality and corruption.

Most people I know are aware of Shakespeare only through an academic context: homework responses, essays, shoddily-assembled presentations in front of bored students. His name and work are synonymous with the blood-stained legacy of centuries of British colonialism, plus the misogyny and racism that can make reading plays like “The Taming of the Shrew” and “Othello” unbearable. I haven’t even gotten to his language, which, while at times beautiful, is also rife with confusing syntax and alarmingly obvious grammatical errors. But just because high school might’ve ruined his plays for you doesn’t mean they have to be ruined forever.

“Revisiting Shakespeare” is intended to offer readers both a guide to and a brief review of Shakespeare’s texts — which audiences may or may not resonate with them, what major themes Shakespeare baked into them, and how they’ve been performed and adapted within the roughly 400 years since Shakespeare has become a thing (see Oskar Eustis’ 2017 production of “Julius Caesar” at the Public Theater in New York City, which garnered lots of controversy for its Trump-like Caesar).

For each play I write about, I’ll recommend some helpful performances and adaptations (novels, etc.) if they’re readily available, as well as academic articles, for those interested in bringing Shakespeare back to the classroom in a more interesting context.

With that being said, I’ve chosen to open this series with one of Shakespeare’s most intense legal dramas: “Measure for Measure.”

The play follows Vincentio, the duke of Vienna, and his appointment of a new deputy, Angelo, while he leaves the city for some time. With Vincentio gone, Angelo begins enforcing the city’s long-ignored bans on adultery and fornication. Swept up in this sudden crackdown is Claudio, who is sentenced “within these three days his head to be chopped off” for impregnating a woman whom he hasn’t yet married. Now on death row (or whatever the 17th-century Viennan equivalent of death row was), Claudio asks his sister, Isabella, a novice nun, to plead with Angelo for his freedom. The twist? Angelo agrees, but only on the condition that Isabella gives up her body and lets him have sex with her. The rest of the play follows Isabella’s fight with Angelo and an ideological clash between Angelo’s cruel legalism and the Duke’s more humanitarian view of the law.

If it wasn’t clear to you immediately, this play is all about justice, morality, and corruption. It asks, is the law meant to teach or punish? Is it right for Angelo to enforce such a harsh penalty upon Claudio? Should Isabella sacrifice her virginity to free her brother? The way the law intertwines with the human body — or, rather, Isabella’s chastity — in this legal drama might remind readers of another (problematic) legal drama from Shakespeare, “The Merchant of Venice,” a play which asks one of its characters to offer “a pound of flesh” as a security demanded on a loan.

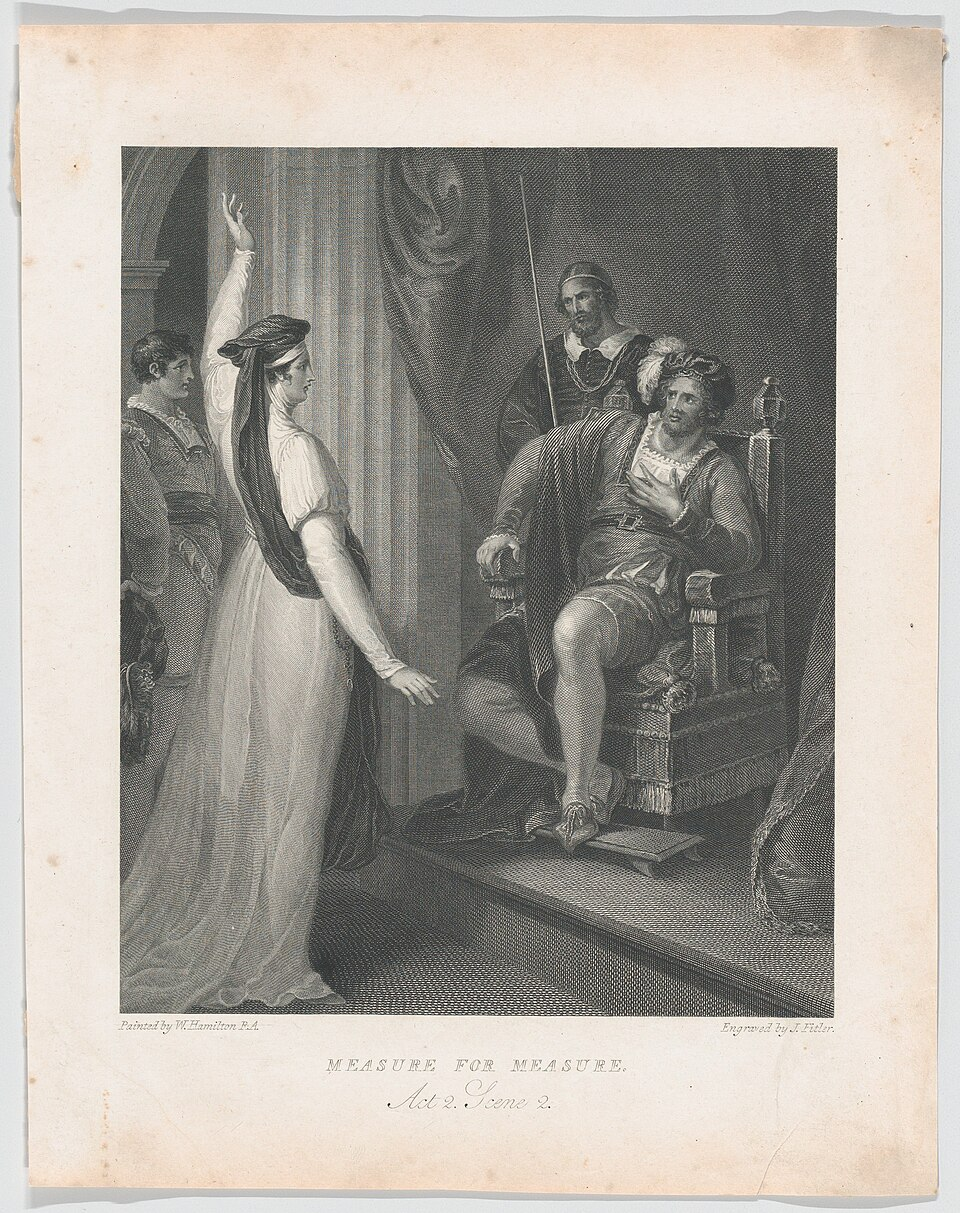

Comparison to other plays aside, what immediately struck me while I was reading “Measure for Measure” was how much Angelo’s villainy resembled that of Claude Frollo in Disney’s “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (directed by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise). Angelo’s soliloquy at the end of Act 2, Scene 2, and Frollo’s song, “Hellfire,” for instance, have some uncanny similarities:

Angelo:

“What, do I love her

That I desire to hear her speak again

And feast upon her eyes?

What is’t I dream on?”

Frollo:

“Then tell me, Maria

Why I see her dancing there

Why her smold’ring eyes still scorch my soul (cogitatione)”

The entirety of Act 2, Scene 2 is arguably Shakespeare at one of his strongest points, where he carefully crafts Isabella’s rhetoric so that she slowly gains more sway over Angelo. At the same time, Angelo finds himself on increasingly shaky argumentative foundations. This is where you get iconic lines, such as:

Isabella:

“O, it is excellent

To have a giant’s strength, but it is tyrannous

To use it like a giant.”

Another key scene is Act 2, Scene 4, which displays similarly powerful craft; Angelo chillingly retorts, “Who will believe thee, Isabel?” after she threatens to expose him for corruption.

That being said, “Measure for Measure” has several issues that might ruin the experience for many people. Despite its incredibly powerful first half, the play begins to falter as it approaches the end, where characters become increasingly reliant on gimmicky disguises and switcheroos to resolve incredibly grim situations. This is especially true for the Duke, who switches between being himself and pretending to be a monk, using the latter disguise to guide Isabella in her fight against Angelo. This ploy continues into Act 5, where both of the Duke’s roles must be present onstage. Resolving this issue involves the Duke finding an excuse to leave the scene so that he can return as the monk, a gimmick which at this point feels irritating. It’s no doubt funnier on stage than while reading, but watching the play that had opened with such psychological intensity lose its dramatic edge was disheartening.

I haven’t even gotten to the ending, which I found so frustrating that it almost completely ruined the reading experience for me — characters that should have been punished go unpunished, and (sorry, spoiler) Isabella is forced into a marriage at the end that doesn’t make much sense. Many will also find that Isabella’s ploy against Angelo borrows from Diana’s ruse against Bertram in “All’s Well that Ends Well,” which involves non-consensual sex. Like many of Shakespeare’s plays, “Measure for Measure” uses marriage to tie up loose ends, although the marriages that end this story often leave more questions than answers.

If you still want to read and watch “Measure for Measure” despite these flaws or, perhaps, because of them, the college provides a few resources for recorded performances (trust me, they’re important, especially if the language is difficult to understand).

One thing to look out for when watching these performances is how they treat Isabella’s silence when the Duke asks to marry her at the end of the play. Traditionally, Isabella’s silence indicates an affirmative answer, although she likely had little agency to choose in the first place. Depending on the performance, Isabella silently smirks at the Duke and accepts his hand in marriage, as seen in the BBC’s 1979 film adaptation (directed by Desmond Davis); or she weeps in silent anguish because she’s unable to protest against the Duke’s authority, as we see in The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC)’s 2019 production (dir. Gregory Doran). These performances can be found on Kanopy and Digital Theatre+, respectively, both of which the college has subscriptions to.

Those with the time and money will be pleasantly surprised that the RSC is actually running a “Measure for Measure” production right now in Stratford-Upon-Avon until late October.

For those interested in a more academic angle, G. Wilson Knight’s essay, “Measure for Measure and the Gospels,” which argues that the ethical standards we see in the play are actually rooted in the Bible’s New Testament (“Judge not, that ye be not judged”), is a good start. Another essay to consider is Jonathan Dollimore’s “Transgression and Surveillance in Measure for Measure,” which argues that sexual transgression in the play isn’t rooted in ethics but politics instead. Emma Smith’s “This is Shakespeare” and Marjorie Garber’s “Shakespeare After All” include more resources for each of the plays, “Measure for Measure” included; both books can be accessed online via Frost Library. The Folger Shakespeare Library also has a further reading page for the play online.

While “Measure for Measure” certainly doesn’t have the same number of performances and adaptations as some of Shakespeare’s more popular plays (cough cough “Hamlet”), nor is it as popular, its intertwining concerns with ethics, religion, and the law will undoubtedly make it a rewarding read for some. For all its technical flaws, jarring tonal shifts, and dark material, this legal drama remains incredibly compelling today.

Comments ()