Race Science, Taught at Amherst

Columnist Willow Delp ’26 uncovers a disturbing chapter of Amherst’s past, confronting how deeply racism was embedded in the college’s academic history and arguing that reckoning with these truths is essential to any genuine commitment to anti-racism today.

In the midst of thesis research on mixed-race narratives, I did not expect an Amherst College connection. While digging through archaic writings on race from the early 20th century, however, I found a journal article from March 1924 by William Gregg, with the telling, unfortunate title “The Mulatto—Crux of the Negro Problem.” Beneath the heading, the publisher notes that, “The author, an Amherst graduate, lawyer by profession, has given much study to race questions in the United States.” Gregg’s comments are unnerving to a modern reader: “The crossing of superior and inferior strains in the vegetable and animal world,” he writes, “gives a progeny superior to the inferior parent although inferior to the superior parent, and the same rule may be expected to hold good among human beings.” Gregg’s writings sparked my latent interest in Amherst’s racial history. Although some attention has been paid to Amherst’s connections to slavery before emancipation, there remains much more to unearth.

It is not surprising to anyone that Amherst, its founding in 1821, did not envision the diverse student population that it boasts today. However, an examination of our history still produces some unsettling details.

Edward Hitchcock Jr., who graduated from Amherst in 1849, eventually returned to serve as professor of hygiene and physical education. He promoted the science of "anthropometry" (“the [historical] study of the human body using detailed measurements”) through his scrupulous measurements of every Amherst student — collecting data on factors such as height, weight, and strength.

Although seemingly innocuous (if not a bit invasive), anthropometry was charged with eugenicist implications — Francis Galton, the founder of eugenics (a notorious racist who referred to Africans as “lazy, palavering savages”), opened his own anthropometry lab.

Additionally, Hitchcock collected data on students’ ethnicities and wrote in 1887 that his measurements could be used to “furnish an average, or a mean, that could be used in an [a]nthropometric study of the Anglo-Saxon race.” When Galton criticized the applicability of Hitchcock’s data, the Amherst professor was deferential to the now-infamous eugenicist: Lundy Braun, Professor Emerita of Medical Science and Africana Studies, writes that Hitchcock “heeded the master’s [Galton’s] request.”

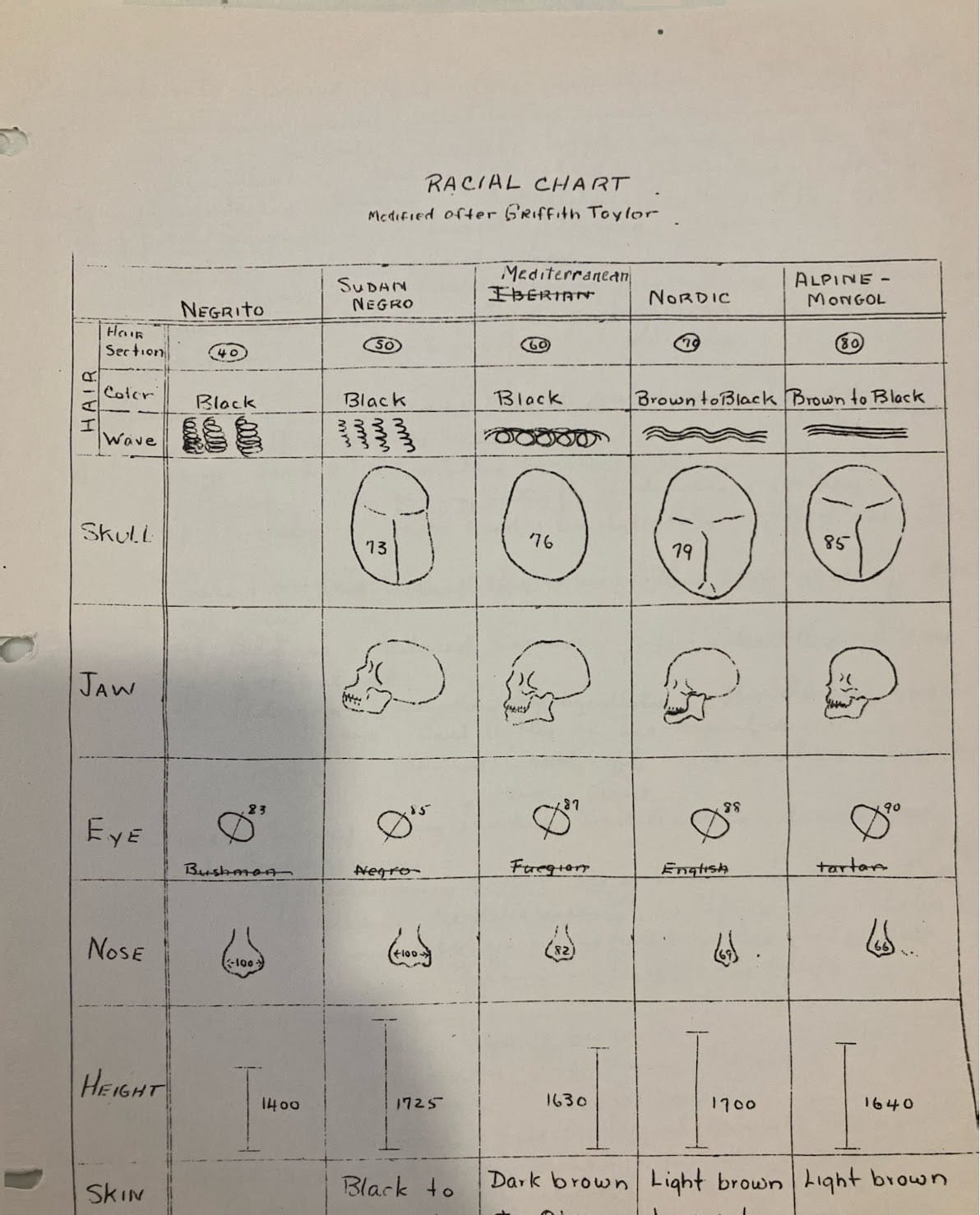

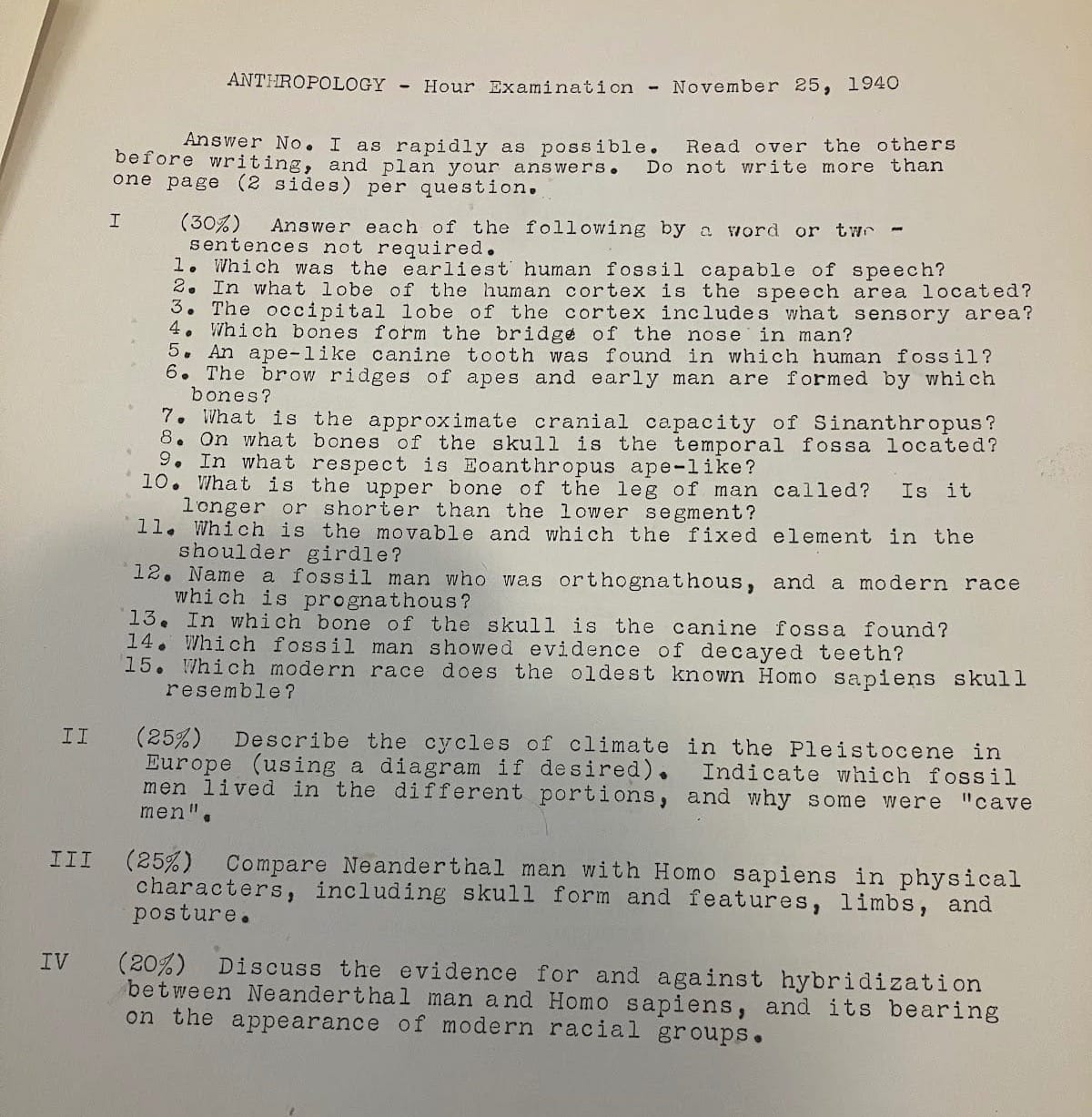

Harkness Professor of Biology, Emeritus and class of 1913 Harold H. Plough provides an illuminating example of the college’s former teachings on race, particularly within the anthropology department — a discipline with its own sordid history far beyond western Massachusetts. A graduate of Amherst, he returned to teach in 1940 with a unit called “Race crossing and its consequences.” The following images are taken from Amherst’s archival collections on Harold H. Plough’s anthropology teachings.

His racial charts included scrupulous measurements of skulls, with categories such as “Sudan Negro” and “Alpine — Mongol.” His 1939-1940 curriculum included a portion on “Measurements of human skulls and cranial capacities.” March 1 was set aside for the “Recording of physical measurements of fellow students.”

Such forms of racial categorization were not innocent scholarly inquiries; they were the very basis of pseudoscientific ideas of racial hierarchy, and Plough’s position teaching at Amherst meant that the school at large implicitly sanctioned such ideology.

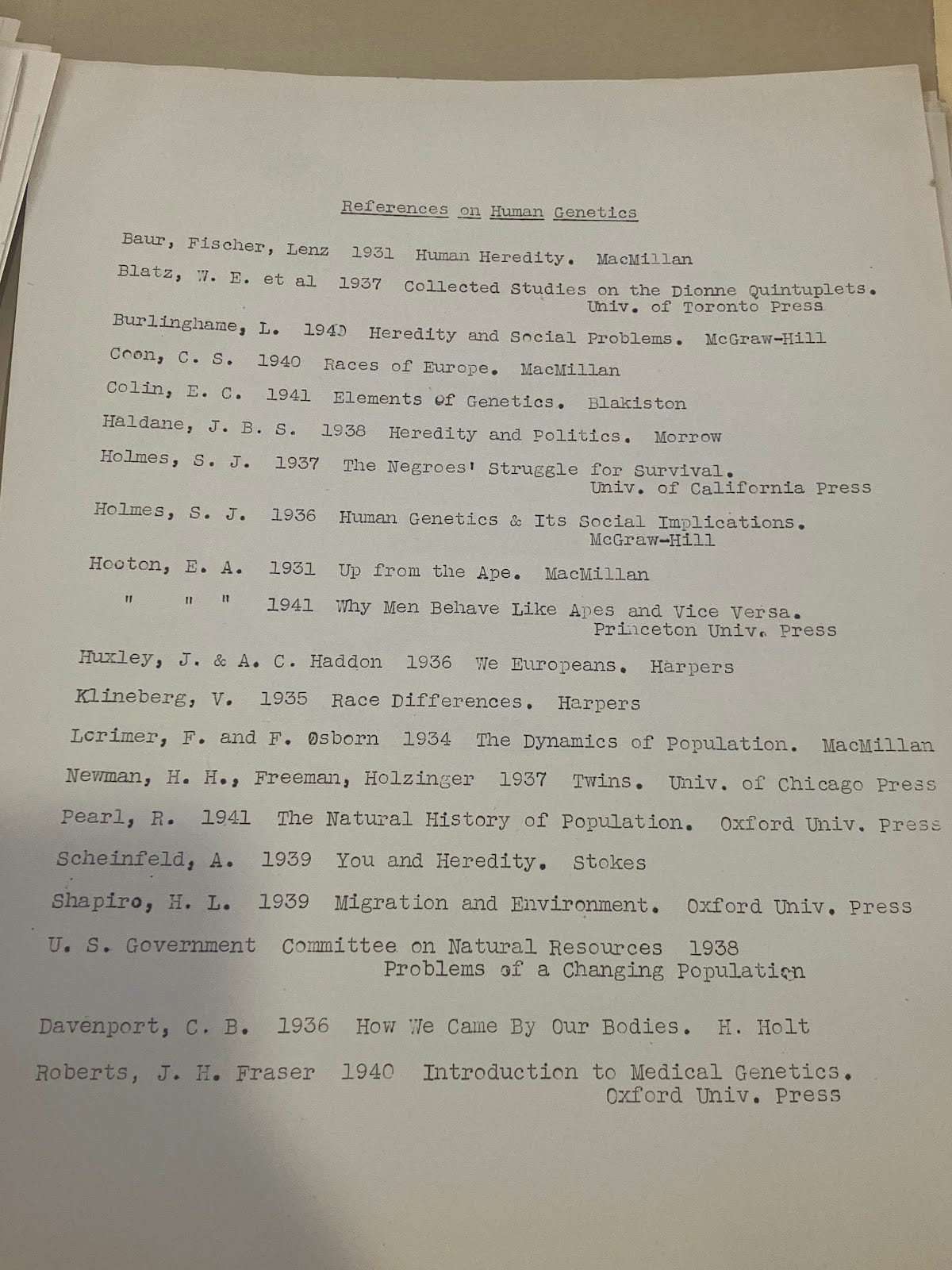

A skim of the texts that Plough suggested for students beneath “Reference and Reading” does not espouse a unified ideology — “We Europeans” by Julian Sorrell Huxley and Alfred Cort Haddon and “Race Differences” by Otto Klineberg suggest a relatively progressive ethos, but the 1921 text “Trend of the Race” by Samuel Holmes paints a vastly different picture.

Holmes begins “Chapter 11: Consanguinous Marriages and Miscegenation” by discussing the marriage habits of the “savage and barbarous peoples.” The chapter is a fascinating, if disturbing, look into the nuances of early 20th-century eugenicist rhetoric: Holmes warned readers of the “social and moral deterioration” of racial mixture, arguing that the “intellectual superiority of the mulatto over the negro” should not induce readers to support “amalgamation.” “The doctrine of the mental equality of black and white does not commend itself to most of those who have had much experience with the colored race,” he wrote, “and it is contradicted by the results of a number of studies on the intelligence of whites and blacks by the application of mental tests.”

Additionally, Plough listed Holmes’ 1937 monograph “The Negroes’ Struggle for Survival” on his list of coursebooks on human genetics. While I couldn’t find the original work, a positive review of the text from 1938 argues that Black people benefited from slavery: “Under slavery, most Negroes were employed on farms and plantations of the southern States and their health was relatively good, but the Civil War changed this.” (The euphemism “employed,” for “enslaved,” is more than disturbing.) Samuel Holmes acted as president of the Society of Biodemography and Social Biology (formerly the American Eugenics Society) from 1938 to 1940.

In 1950, Plough was elected to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. His legacy, as currently captured on the Amherst College Oral History Project (as of the time of my writing) via a 1977 interview, belies any racist past teachings. He laments the difficulties experienced by Black students, noting that they “were all particularly capable people.” Perhaps he had a change of heart, or perhaps, after the Civil Rights Movement, he realized that his former lectures would not be viewed positively by a changing nation. He died in 1985, and his only published book was wholly unrelated to race: “Sea Squirts of the Atlantic Continental Shelf.”

Amherst was certainly not unique in having a racist history. However, if our commitments to anti-racism are genuine, we have to be able to acknowledge when we have faltered. As I continue to explore the work and legacy of prominent Amherst alumni and former Amherst professors, I hope to keep shining a light on when the school has failed its students of color. Knowing our dark past will help us work towards a brighter future.

Editor's note, Oct. 22, 2025: Photo captions were updated to best reflect the contents of each photo.

Comments ()