Old News: October in 1880

In this edition of Old News, Managing Features Editor Mira Wilde ’28 and Staff Writer Sofia Angarita ’26 examined an October 1880 issue of The Amherst Student, revealing debates of campus culture, comments on national politics, and traditions that defined Amherst nearly 150 years ago.

Welcome back to Old News! In this column, we use a random number generator to select a year in the college’s history and take a look at The Student’s issue from this week in that year. Read more about this project in its first column here.

This Week’s Year: 1880

This week’s Old News takes us back to Oct. 9, 1880, when Amherst students filled the pages of The Student with spirited debates about religion, sportmanship, and politics — all while juggling the antics of campus traditions like “The Cider Meet” that feel both foreign and familiar today. The issue opens a window into a college alive with civic and campus engagement: students arguing about compulsory chapel attendance, teasing rival schools, and forming partisan clubs as the nation braced for the presidential race between James Garfield and Winfield Scott Hancock.

What stands out about this edition the most is how recognizable the Amherst voice remains — witty, opinionated, and eager to weigh in on everything from chapel clapping to library decorum.

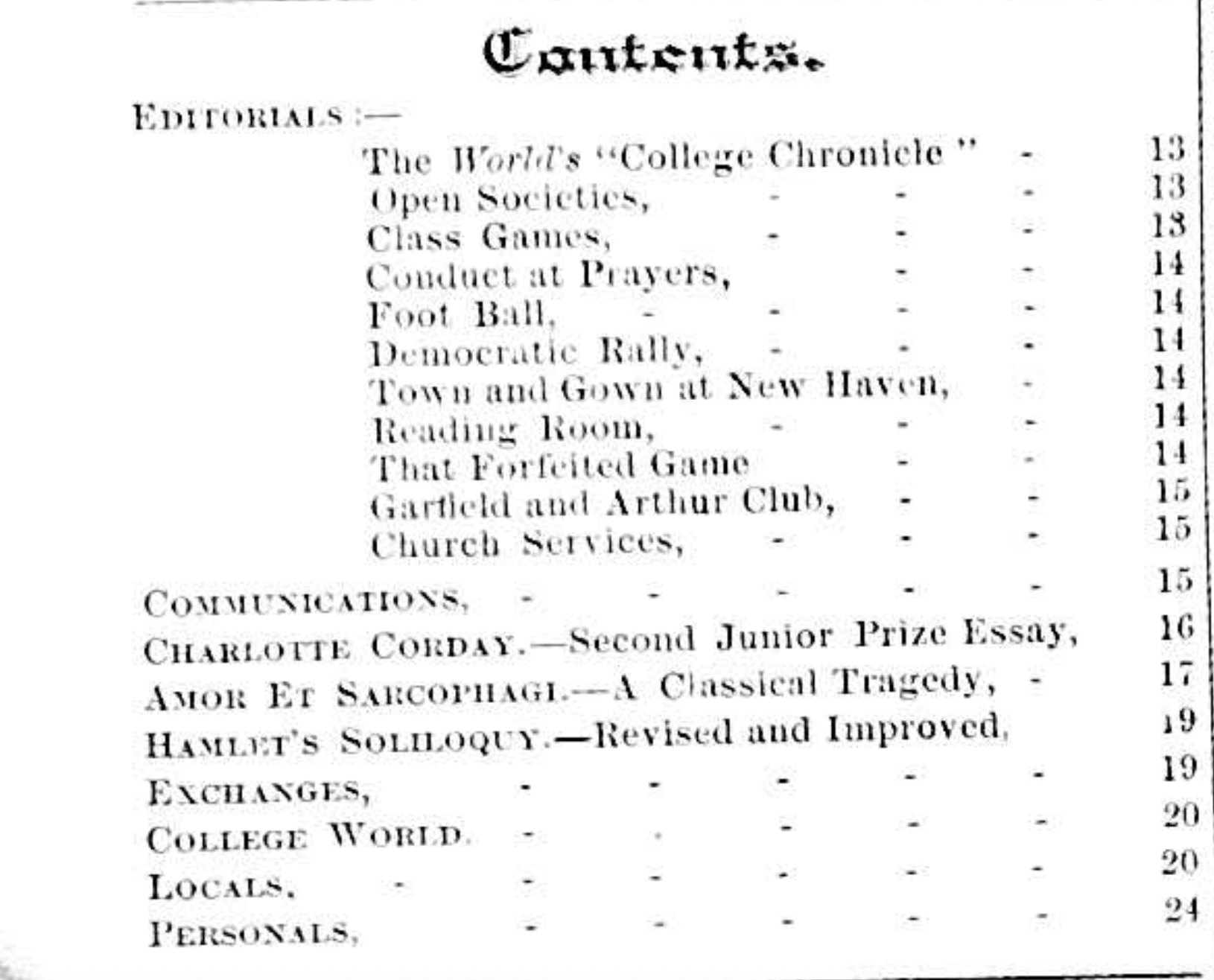

“Editorials”

Student use of the anonymous social media app Fizz has been the site of controversy since its arrival on campus in 2023. In a September email titled “Democracy Day and Campus Culture” sent to the Amherst College community, President Michael Elliott addressed student use of Fizz by arguing that anonymity, even when protected as free expression, threatens our ideal intellectual environment. Fizz moderators review submissions after publication, and in some cases remove inappropriate posts. In 1880, editors of The Amherst Student approved anonymous submissions prior to publication. The ability to “take down” problematic Fizz posts marks a key difference between a newspaper publication and an anonymous college app: Once approved and published, these editorials were preserved in their original format for us to read 145 years later! Even then, anonymity was a source of major controversy on campus. In this week’s Old News, we’re sharing four of the most notable entries into the “Editorial” section, the opinion section of the 1880 Student.

- Open societies

The Athenian and Alexandrian societies were the first student-run societies at Amherst. These two literary societies were open to all students and promoted student engagement through writing, debating, and social events. Their dominance on campus was later challenged when secret societies emerged in 1830, sparking decades of rivalry between secret and “anti-secret” groups — a trend mirrored at other colleges around the country. In an op-ed titled “Open Societies,” an anonymous writer lamented the prominence of secret societies: “If, as is said, the secret societies are sapping the life from these older organizations, then it is a sorry day for the college.” The author also noted the ridicule directed toward the Athenian and Alexandrian societies: “It has been fashion of late to laugh at these time honored institutions,” he wrote. Still, the writer remained confident that the open societies would prove their worth through Hardy Prizes — awards established by Board of Trustees member Alphesus Hardy for “excellence in extemporaneous speaking.” Winning a Hardy Prize, the author argued, would show that Athenian and Alexandrian societies — not their secret competitors — best embodied Amherst’s ideals and would therefore “laugh longest.”

- Conduct at Prayers

Another anonymous writer complained about misbehavior during church services. He wrote, “The students have been repeatedly urged, through our columns and otherwise, to manifest more interest in musical matters. We still adhere to our theory, but when certain students attempt to beat time to the singing during prayers, it seems to us that their enthusiasm is carried too far.” This op-ed writer suggested that students find outlets for their loudness other than clapping during the musical portion of prayers. The writer ominously concluded, “We hope that the slight disturbance which occurred a few mornings since at the chapel will not be repeated.”

- “Foot Ball”

In the 19th century, anxieties about declining male athleticism plagued New England colleges. This anonymous writer, although not a fan of intercollegiate sports, displayed concerns about athleticism at Amherst. He confessed that intercollegiate games, “[would] have a tendency to create more of an interest in out-door sports, of which there has been an alarming lack in the past.” In 1880, one Amherst College remedy for these anxieties involved a mandatory gym program and taking anthropometric measurements of students. The author, however, cautioned against playing football games against other colleges, advising that competition remain internal — between class years within Amherst.

- Reading room

On Fizz today, students sometimes call out people who are acting disruptively in the library or dining hall. This practice dates back to at least 1880, and I wonder if, despite one author’s anonymity, others knew the perpetrator addressed in their article. He wrote, “If there is anything disagreeable in the world to one reading, it is to have a fellow try to read the same paper over his shoulder, yet there are some who haven’t common decency enough to know better than to insinuate their heads into places where they are not wanted and to lean their clumsy bodies upon others so as to greatly inconvenience them.” Deemed a “less bad” habit than over-the-shoulder reading, the anonymous author also complains about smoking in the reading room. “We scarcely need repeat the remark so often made that smoke is unpleasant to some men. Certainly, a gentleman would have sufficient regard for others to refrain from this habit in a public place. To those other than gentlemen, we can only say that you are not the only ones who have feelings.” This author demanded a little empathy for fellow non-smoking students, over a hundred years before indoor smoking bans were first enforced in the United States.

The Presidential Election of 1880: Garfield vs. Hancock

Many pages of this October edition of The Student were dedicated to the upcoming presidential election. Republican Rep. James Garfield of Ohio was vying for the seat in the White House against Democratic candidate and Union General Winfield Scott Hancock.

In another editorial, titled “Garfield and Arthur Club,” a student celebrated the recent formation of the political club on campus. The author did not express any support for the presidential and vice presidential candidates, and instead lauded “the spirit which prompts the formation of a political club, of either faith.” He reasoned that this zeal for civic engagement and desire to stay involved in national politics was an exemplary way to take advantage of the liberal education received at Amherst.

With a message that still remains relevant, the writer later called on students to adopt healthy inquiry that would shift the focus of the college from theory to practical matters: “Let every student remember that it is the superabundance of theory and the lack of practical knowledge which the young collegian is apt to display that makes any practical business men point almost with scorn to a collegiate course.”

The Garfield and Arthur club was also mentioned in the “Locals” section of the paper: “There will be a Garfield and Arthur campaign meeting at College Hall next Monday night at 8 P.M. Speeches may be expected from Pres[ident Julius] Seelye and others. A torchlight procession will precede the meeting.” The actions of the political party seem foreign to the expectations of democratic engagement we see today, especially in regards to the college president speaking at a partisan event. The section also reported on a Democratic flag-raising that had occurred the previous Friday. These events usually included a speech and a symbolic raising of a flag customized in support of a political party’s candidates. The paper referenced the approving raucous that followed the speaker's declaration that Hancock was “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

The final piece of election commentary in this issue responded to a controversy that had erupted at Yale University earlier that month. On Oct. 2, The Yale Record published a front-page article titled “The Great Outrage,” detailing a scandal that quickly made its way to other campuses. During a Sigma Epsilon initiation, several sophomores pulled down and tore up a Hancock campaign flag belonging to the Democrat-affiliated Jeffersonian Club. What might have been dismissed as a college prank soon escalated into a political incident, as Yale’s Democratic students and local press denounced the act as partisan vandalism.

At Amherst, the incident drew an indignant response from an anonymous writer. In an editorial labeled “Town and Gown at New Haven,” the author condemned what they saw as the hypocrisy of Democratic outrage, writing that “the Democratic press and Democratic party leaders, those very virtuous parties who quietly smile and nod approval when a negro is murdered at the South, are holding up their hands in holy horror because, forsooth, a thoughtless band of students, in the midst of a hilarious initiation, tore down a Hancock flag.” The tone of the response reveals how intertwined collegiate culture and national politics had become — and how partisan tensions found their way even into cross-campus rituals and rivalries.

Lost Traditions

This edition of The Student also made casual references to old (and sometimes extinct) Amherst traditions. Of specific note were allusions to Mountain Day, the aforementioned Cider Meet, and the Sabrina statue. The “Locals” section of the newspaper reported: “Mountain day last Thursday. Everybody enjoyed themselves thoroughly.” This tradition — which is meant to give students a day off from school to enjoy time in nature — began with an 1845 hike to the summit of Mt. Holyoke led by then-President Edward Hitchcock. For the next couple of decades, Mountain Day was an unfixed date that occurred sometime during the first half of October. The first official Mountain Day was held in 1874; in 1899, the first Thursday of October was officially designated as Mountain Day. The day disappeared as a tradition at Amherst in the early 1930s and has yet to return, despite its continued relevance at surrounding colleges.

Unlike Mountain Day’s legacy, the legacy of the Amherst Cider Meet (not to be confused with this past weekend’s Cider Run) is isolated to the archives. Also found under “Locals,” The Student relayed that: “All those who can walk, run, jump, or do anything else extraordinary ought to go in and help get the barrel of cider; and the best of the college ought to be on hand to encourage the contestants with their applause.” Further investigation into the Amherst archives revealed that the so-called “Cider Meet” first occurred in 1778 as a field-day-esque event hosting various competitions between classes, including a three-mile walk, three-legged and blind wheelbarrow races, and a greased pig-wrangling competition. At the occasion’s inaugural event, 800 students were in attendance, including many spectators from nearby Smith College.

The final Amherst tradition that makes its appearance in this 1880 edition of The Student is the well-known thefts of the Sabrina statue. In the “Locals” section of the paper, it was reported that “Sabrina has again disappeared. Some bright [s]ophomores succeeded in throwing her into a ditch and covering her with a little dirt.” In response to this event, faculty suggested that the statue be better protected going forward, but these plans never came to fruition, as the statue was kidnapped many more times in the same year. To put a stop to the antics, then-President Seelye instructed Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy Charles Garman to smash the statue — an act that he disobeyed, instead keeping Sabrina in his barn until she was found in 1887. While Seelye had his ideas about how to deal with the Sabrina heists, The Student offered their own two cents: “We would suggest to the Faculty, that Sabrina be filled with lead, surrounded by man traps, and be attached to a spring gun. She might then remain undisturbed.”

Miscellaneous

In the Oct. 9 edition of the 1880 Student, the first three pages of the paper served as an anonymous forum to air grievances, call out other colleges, and reflect local reactions to national issues.

In one column called “Exchanges,” the author engaged in a smack-talking battle with the “Princetonian” about the success of Amherst sports: “We beat them twice without much trouble, and had reasonable expectations of repeating the ceremony.” While The Student was utilized to engage in cross-campus battles about athletics, “Exchanges” also commented on the articles and style of other schools’ newspapers. While the author praised the well-written articles of the “Notre Dame Scholastic,” he also critiqued the layout: “The style and arrangement of the paper are very unattractive.” One can only wonder what other surrounding papers were saying about The Student’s sassy publication at the time.

This Student had updates on Yale and Harvard’s newly extended Sunday afternoon library hours, an announcement of Williams’ new college president, and a report on the 25,000 bushels of clams Vassar consumed the previous year.

The use of The Student as a platform for short reflections on specific events, aspects of campus life, and issues outside of Western Massachusetts differs from how the newspaper operates today. With the paper’s current emphasis on well-researched articles about local issues, the 1880 edition of The Student stands in stark contrast as a more casual way of communicating among Amherst and to other students outside of campus.

What did these older articles make you think about? Did they give you any insight about Amherst and the world then? Now? Send your thoughts in at bit.ly/amherstoldnews. We’d love to feature reflections.

Comments ()