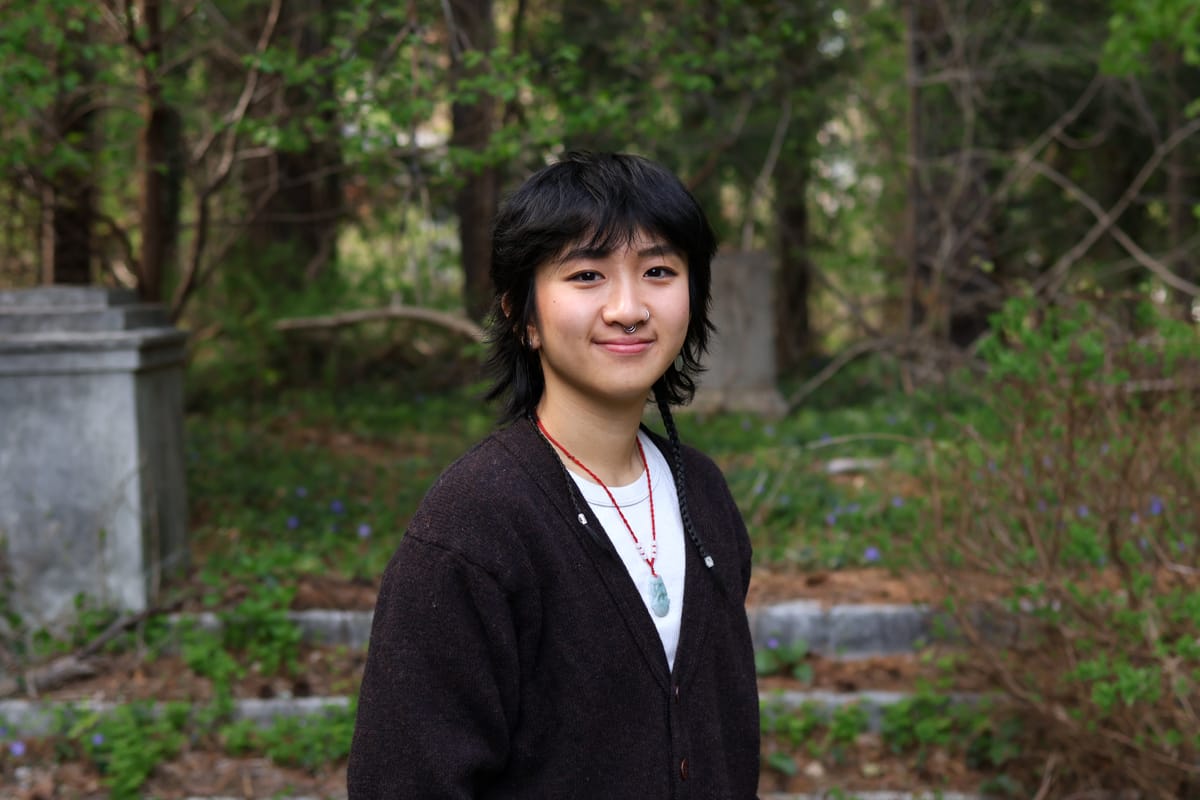

Kei Lim: A Profile of Objects

Wandering through their apartment, you can glimpse who Kei Lim is — curious, deeply reflective, and full of care for the people in their life.

When I first stepped into Kei’s apartment, I was taken aback. They had warned me they had a lot of things in their apartment, but I was not expecting this — a two-foot-tall wooden well placed on a ledge; a side table with baby dolls carefully arranged inside its glass top; and so, so many different versions of Bananagrams. Plus, a cat — adorable, overweight, three-legged — hopping around it all.

I walked around, peering at the tchotchkes and books and Polaroids, but what surprised me most was not the amount of things. If you know Kei, you know they have a bad memory — but no matter what I pointed at and asked about, they knew the full story.

For example, a wind-up teddy bear with a blue ribbon — the girl they sat next to on the bus in kindergarten gave it to them before she moved. Another one, red-haired troll atop a lampshade — Yasmin Hamilton ’24 gave it to them during The Student’s annual editor holiday gift exchange.

So when we sat down for this profile, back in their apartment in Greenfield, I started by asking them how they could remember so much about these objects when they could remember so little generally.

“Objects unlock memories for me that I wouldn’t otherwise have access to,” Kei said. “The only things that I can remember before I was 12 are tied to the objects that I have.”

As we continued talking, they referenced objects around the apartment as a way to explain their feelings, relationships, and pivotal events.

Our interview (which spanned six hours, during which Kei cleaned their bathroom, refilled the cat’s litter box, and checked their mailbox) was not linear. At many points, we got distracted or went on a long tangent (OtterAI, The Student’s transcription service, summarized the interview recording as “interspersed with practical tasks and side comments”). Many things could not be included (Did you know Kei has an immense knowledge of 19th-century bonbon spoons through their two-year stint working at the Emily Dickinson Museum?)

The throughline of our conversation was never linear time — rather, Kei’s experiences came out in reference to the objects that made them.

***

On the table is a pocket sudoku book, half-filled out. You might have seen them with it in the newsroom when they were bored. Or perhaps you saw them sitting in Val methodically recording their start and end times in the book (I would be surprised if you saw them in Val — they’ve lived off-campus since their second semester of college, so they can only eat there through a guest swipe or when they work over the summer).

If you met Kei in college, you might not realize how much they love math. Much of their focus now is on writing and editing, but believe it or not, they used to be a STEM kid back in Ohio. By their sophomore year at their Catholic all-girls’ high school, they had maxed out of the available math courses because they were three years ahead in math.

“I [found math] fun, because it was very much like puzzles, and I liked puzzles and patterns,” they said.

But just because they did well in math and enjoyed it didn’t mean that Kei was a natural. When they were a kid, their mother enrolled them and their brother, Victor, in the same activities (science fairs, violin, golf, and chess, to name a few).

“There was a period where all the things that my brother was good at, I wanted to be good at,” they said. “He was very good at quantitative analysis and stuff like that … I was always working really hard to try and be as good as he was at those things.”

What did come naturally to them was reading. As a kid, they devoured books, checking out 12 at a time from the public library every week, and when they finished those, they would turn to the books on Victor’s shelf. A couple times, when even that failed, they would steal school books from his backpack.

Kei also described how their parents grew up poor in Malaysia and worked hard so that Kei and Victor could have a successful future.

“I [wanted] to live up to their expectations … out of gratitude, and also in a sense out of obligation,” they said.

Eventually, when they hit seventh or eighth grade, Kei shifted their priorities. For years, they had done what their brother had been interested in, but at this point, they wanted to explore new things.

“It wasn’t necessarily that I was trying to rebel,” Kei explained. “I [realized] that everything was interesting, and I want[ed] to both get to know the [community] around me and get to know what they care about.”

They also wanted to interrogate the value of what they were learning in the classroom.

“Why does any of this matter? How am I actually going to apply any of this stuff? In order to figure that out, I had to go and work and also engage in clubs that engage with the community,” they said.

Outside the classroom, Kei stayed busy: working jobs that taught them skills from pizza-making to drawing blood; leading Student Council and community organizing — getting involved in the lives of those they cared about.

Later in high school, Kei developed another interest: economics. They had started reading books related to the social sciences in their free time and were interested in the authors’ conception of people operating within societal systems, so they decided to take A.P. Economics their junior year.

“This form of modeling is interesting to me … especially because it’s not necessarily the primary way that I conceptualize the world. [But] it’s inherently important to understand,” Kei said.

The teacher, Elizabeth Gromada, was amazing. She did not let Kei coast, and they learned how to think critically. The class was a big reason why Kei decided to major in economics later. It was a new lens for them to think about the issues they care about, and they wanted to spend more time with it.

“I feel like we can’t think about how to care for people, whether on an individual level — like our families — on a community level … or even in a diasporic sense, without thinking about economics — because we can’t think about how we function as members of society without thinking about things like productivity and resource allocation,” Kei said. “In a capitalist society, that feels quite important.”

***

Hundreds of word magnets cover Kei’s refrigerator. Friends who have visited have made little phrases and poems with them.

Before Kei came to Amherst, they weren’t very interested in writing.

(Kei was the editor-in-chief of their high school newspaper, however. They are full of contradictions.)

High school English classes were not stimulating and felt “redundant” to them. However, when they got to college, they wanted to try out different disciplines.

Kei took English classes, interested in seeing how people could “communicate the same ideas using different modes of language.”

“A lot of my writing has been … thinking about what figurative language is ‘allowed’ in creative writing that’s not allowed in critical writing. What can that do in terms of explaining the ways that we see the world?” Kei explained.

They had never tried creative writing before college, but they started writing poetry and took courses in the department, ending up accidentally majoring in English.

For the past couple of years, they have been exploring Asian American joy in their work. In high school, they had read “Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation” by David Eng and Shinhee Han, which explores intergenerational grief in Asian American families.

“I noticed that a lot of the Asian American writers I read … their writing is laden with grief and sometimes anger,” Kei said. “[But] Zora Neale Hurston and other writers conceptualize these notions of like queer joy and Black joy. [I am curious] whether there is a similar notion of [racialized] joy that can be conceptualized … for Asian American people.”

Though they enjoy writing, Kei said that they feel it is not necessary to them in the way they’ve observed for many others at Amherst.

“Some people that I know have this innate need to write,” they said. “For me, it’s more like, ‘Oh, this is fun, because language is fun to play around with.”

Kei enjoys editing more than writing. They had edited their friends’ papers and even their brother’s college essays (when they were 14), but it was at Amherst where they got to really hone their editing skills.

“[I love] semantic patterns and grammatical rules … editing kind of feels like a puzzle to me,” Kei said. “We have a certain lexicon of words, and it’s like, ‘How do we best communicate ideas, whether that’s an op-ed or a piece of poetry?’”

Before the end of their first month at Amherst, they were an opinion editor on The Student. In their exit letter published last semester, they wrote that “My relationship with The Student is possibly the longest, and most consistent, relationship I’ve had at Amherst.”

Kei rose through the ranks alongside their dear friend and “work spouse” Dustin Copeland ’25, becoming a senior managing editor and, eventually, editor-in-chief. Dustin said that the pair worked well together because they were both flexible in the newsroom.

But of course, staying up until (at least) 2 a.m. every Tuesday and managing dozens of editors and writers was not easy.

“It’s a little puppy that keeps peeing all over the place. And as many times as you take it outside and teach it where to pee, it just keeps peeing inside … but it’s a little puppy, so you still love it,” Kei said, describing The Student.

At both The Student and Cosmic Writers — a creative writing youth education nonprofit they work at — Kei’s favorite part is helping people develop their writing skills through teaching. They particularly like working with kids — both because they love children, and also because they have not started “overthinking” their writing styles.

“When [kids] write for the first time … it comes out in a very raw, visceral way that is very true to the emotions they’re experiencing,” Kei said. “It’s really cool to work with them on how to use language to express these emotions or to make an argument. How do we use our anger to produce writing that can change the way that like someone looks at something, or can make someone feel your emotions as if they were their own? That’s extremely rewarding to see and to work with.”

They also work at The Common, a literary magazine based in Amherst. They started in their sophomore fall and are currently the Applefield Fellow.

While Kei enjoys the many different tasks they do that are necessary to a small publication — editing, fundraising, marketing, event coordination, analytics — their favorite part is streamlining The Common’s operations.

“The greatest cause of my joy when working for The Common is reworking how we do certain things,” Kei said. “What are effective social media strategies? What do we do with this information that we have about the people who read The Common? How do we word language differently in order to make people care?”

***

At some point when they’re cleaning, Kei finds their placard for the Collin Armstrong Poetry Prize (they have won it three times in a row — this one is from 2025). “I need to throw this out,” they mutter. I’m shocked — they have relics from when they were four, but they won’t keep their award?

Kei has won numerous awards over their life. But there was no sign of these achievements anywhere in their apartment. I asked Kei why they don’t seem to keep any of them.

Kei didn’t seem to understand why I was so perplexed. “I think that everyone likes recognition in some capacity, but I think that I prefer that on a more personal level,” they explained. Kei was reluctant to say they were proud of anything — not the awards, not their apartment, not even The Student.

“It feels weird to be proud about specific outcomes because there are always millions of different outcomes and possibilities,” Kei said.

But if they had to pick something they are “proud of” (let the record show that Kei would not even say they are “proud” of this), they would say the relationships they have formed.

“It’s not necessarily that I’m proud of my relationships and how I act in them, but [it’s] the work that I do put into them, and the care,” Kei said. “I would say that[’s] the closest I get to being proud.”

In middle school, they noticed how a lot of people treated relationships as transactional, and became very intentional about who they were friends with to avoid this.

“I’m proud of the people that I am friends with — not [necessarily] their accomplishments, just that I genuinely believe that the people that I'm friends with are good people,” Kei said.

Kei is a devoted friend, dropping everything whenever anyone needs help. Someone is stranded at the train station? Kei is cancelling their plans to pick them up. Someone going through a breakup? Kei is there with Friendly’s milkshakes and trashy reality TV shows. When I got food poisoning two months ago, they took care of me, alternating between feeding me soup and Gatorade and holding my hair back as I vomited.

They also don’t give up on their friendships easily. This tendency can be a good or a bad thing, but it means that they invest a lot of time into people and are very reflective of their relationality and how they operate in friendships.

Kalidas Shanti ’22 said that, unlike many friends he has, he never has to think through how he acts around Kei. He can show up in whatever state or mindset he is in, and Kei will meet him there.

“We’ll go somewhere that is meaningful and fruitful to both of us, and I don’t always know that that’s going to happen with other people,” he said.

***

Kei wanders to a ledge where there are more than a dozen rocks in a turned wood bowl that they made last summer at the Eagle Eye Institute. They take out a couple, feeling the ridges of each.

On the first day of “Environmental Anthropology,” a class Kei and I shared this semester, we were given the icebreaker: “What was your first conceptualization of nature?” Many people said Earth Day celebrations, or going on hikes in the woods. Kei had a different answer. They always knew the difference between outside and inside, but they never conceptualized “nature” as distinct from society because everything was interconnected.

(Every time Kei said “nature” or “natural world,” they put it in air quotes, so I will use quotation marks as well.)

“It wasn’t just [that I was playing] in the dirt and with the bugs and the grass,” Kei explained. “I was watching cars on the road [and noticing how] the trees would still extend over the road in some capacity. [Or how] birds would nest on buildings … It was very clear to me the ways in which everything was interacting with everything else.”

They also thought part of this stemmed from how, though their parents were not very religious, Buddhist teachings about “nature” seeped into their worldview.

“You could be reincarnated as anything. So it feels like we can’t be that separate and distinctive [because] in another life,” Kei said. “I was one of those kids who wanted to be a shark when I grew up, except I actually believed that [I could in another lifetime].”

As they grew up and learned more, this conceptualization of “nature” never substantially changed. They see the ways “nature” and society are distinct through the legal, political, and sociocultural structures that separate them, but their personal experience of the two is still intertwined.

This approach is part of why Assistant Professor of Anthropology Victoria Nguyen wanted Kei to be her research assistant last spring. “I thought Kei would be a really interesting student to work with [because] I really wanted a thought partner,” she said.

Before they got to Amherst, they thought they would do something professionally with this interest in the “natural world” (they still flirt with the idea of becoming an entomologist).

However, in college, writing, extracurriculars, and jobs became more of a priority. So when they were figuring out what to do during their last Amherst summer, they decided to try out something new that was connected to “nature.”

They did land management work at Bob Saul ’80’s tree farms and at the Eagle Eye Institute in Peru, Massachusetts. They would get up at 6 a.m. to drive to Eagle Eye, drive back at lunchtime to Amherst to work for The Common until 5 p.m., and then work on the tree farms after that, or on weekends.

Kei hated the inevitability of bug bites and poison ivy, no matter how much they covered up. But they also loved working with their hands outside and the people they worked with.

“I was really, really happy that summer,” Kei said.

***

We leave the apartment, still recording.

Kei doesn’t know what’s next for them. For the next year, they will be The Common’s Literary Editorial Fellow, but after that, they have no idea. Maybe they’ll continue working in publishing or editing. Maybe they will teach again. Maybe they’ll return to STEM. But for Kei, that uncertainty isn’t a bad thing.

“I see them just really being present … and really being comfortable with where they are now,” Nguyen said. “That means not knowing all the answers or knowing everything that the future will hold, but just [having] this quiet conviction that it will all work out as long as they situate themselves where they feel most centered, most grounded.”

Comments ()