Daffodils to Drones: Reading Outside the Western Canon

Staff Writer Amaya Ranatunge ’28 explores how Arabic and Arab diaspora poetry at Amherst challenges the Western literary canon by tying art to activism. Discover this form of poetry that refuses silence by insisting on being heard even in the face of oppression.

Growing up in a curriculum that insisted poetry was shaped entirely by classical European traditions, I thought poetry began with William Wordsworth and ended with William Shakespeare. Poetry, I was taught, was beautiful because it was distant: because it described Grecian urns, nightingales, and daffodils that belonged to another world. Regardless of how ethereal these poems sounded, they never spoke of experiences I recognized. They carried no traces of migration, colonization, or the hybrid identities that defined the lives of non-Western communities. Fortunately, it turns out poetry doesn’t stop at the English countryside. After studying poetry at Amherst, I’m learning that there’s a whole world of verse beyond Shakespeare pining over heartbreaks or Wordsworth having a spiritual crisis over a lake.

The most recent non-European poetic tradition I’ve encountered is Arabic poetry. In part, this is because the war in Gaza has brought renewed attention to Palestinian and Arab voices, reminding us how art becomes resistance in times of oppression. But it’s also because Amherst itself has started creating more spaces for Arabic literature, through new courses and events that center transnational perspectives. “Poetry Writing I” with Writer-In-Residence George Abraham was an integral part of my learning process, during this class. Reading Arabic poetry felt like stepping into a world where words carry both the weight of history and the pulse of survival. In that class, we read poets like Fargo Nissim Tbakhi, Refaat Alareer, Tarik Dobbs, Sarona Abuaker, and many more. What struck me about these poets was how unapologetically political their work is, and how they weave together art and activism. Their poems don’t try to be beautiful; they try to be meaningful and honest. They spoke of loss, occupation, and identity with a kind of emotional precision and relatability I hadn’t encountered before.

I was most interested in reading different works of modern Palestinian poets that acted as a voice of resistance, critiquing the war in Gaza. For them, poetry was not just art, but a tool for sociopolitical activism. The foreword of an anthology we read, “Heaven Looks Like Us,” captures this feeling perfectly: “From the singular wound of our becoming Palestinian, we emerge as mirror and agitator. We live our deaths in exile, trespassing border after failed border, presencing ourselves in every tongue that fails to hold the weight of us, translating wound into word into world.” Reading their work made me realize that the concept of “art for art’s sake” — the idea that art exists purely for beauty, detached from politics or social realities is largely a luxury. But for Palestinian poets like Refaat Alareer, poetry is not just decorative; it is a form of survival. As he once wrote in his poetry and prose collection “If I Must Die,” you have to “believe in the power of literature changing lives, as a means of resistance, a means of fighting back.”

I got to see this idea come to life at “An Evening of Transnational Arab Literature and Arabic Music,” held on Oct. 2 in Converse Hall. The event featured the Palestinian poet Sarona Abuaker and the Lebanese-Syrian poet Tarik Dobbs alongside live music from the Layaali Music Ensemble.

Tarik Dobbs read out poems from his collection “Nazar Boy.” One poem that stood out to me was “Poem Where Every Drone is a Bird,” a haunting piece about Israeli airstrikes on Gaza. It’s a visual poem, arranged in the shape of a tree, where branches of text twist upward to mirror both nature and destruction. On the page, the poem looks almost serene until you begin reading and realize that the “birds” are drones, forming a “wall of murder” in the sky. That tension between form and meaning is exactly what makes visual poetry so powerful: It doesn’t just tell you about violence; it makes you see it. The poem becomes both art and protest, its shape forcing you to confront how beauty and brutality coexist. In that sense, Dobbs’ work reminded me how Arab diaspora poetry often uses experimentation not for aesthetic play, but as a didactic act, asking us to read beyond comfort and to feel the politics embedded in every line.

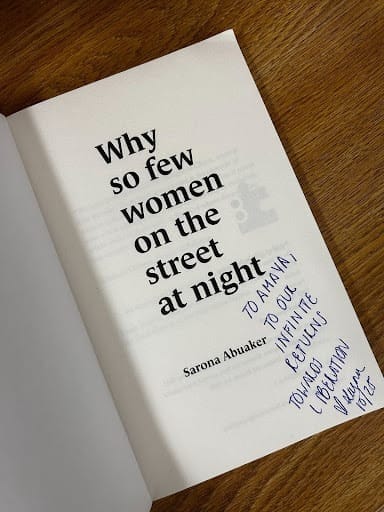

Out of all the readings that night, Abuaker’s reading moved me most. Her collection “Why So Few Women on the Street at Night” explores queer Palestinian futurisms while wrestling with questions of safety and belonging. Listening to her read was unlike any poetry reading I’d been to before. Her voice carried the emotions conveyed by the poem perfectly. One of the closing poems from her collection, “SLUG OPS,” captures this tension vividly. The poem begins with the innocence of a childhood memory of watching her cousin salt a garden slug. However, the image is immediately disrupted by the intrusion of war, as soldiers raid the family home. What begins as a small act of cruelty transforms into a haunting metaphor for militarized destruction: “once the salt draws / the water out from the slug / it bursts into flames … the slug is an incendiary munition.” In her poetry, no landscape remains innocent; every image carries the weight of surveillance, invasion, and grief. Afterward, I asked her to sign my copy of her book. She wrote, “To our infinite returns towards liberation.” That inscription has stayed with me ever since.

Today, that line has come to define what Arabic poetry means to me. It captures a transformative return to memory, community, and language. Through Abraham’s class and that October evening reading, I learned that unless you’re safe and privileged enough to treat art like decoration, poetry doesn’t exist in isolation from the world or its politics. Poetry converses with the world, challenges it, and sometimes even heals it. Arabic and Arab diaspora poetry, in particular, resists silence; it demands to be heard, even when the world looks away. And perhaps that’s what makes it so vital to study here, at a place like Amherst, because it reminds us that literature isn’t a luxury of peace, but a language of persistence marking “our infinite returns towards liberation.”

Comments ()