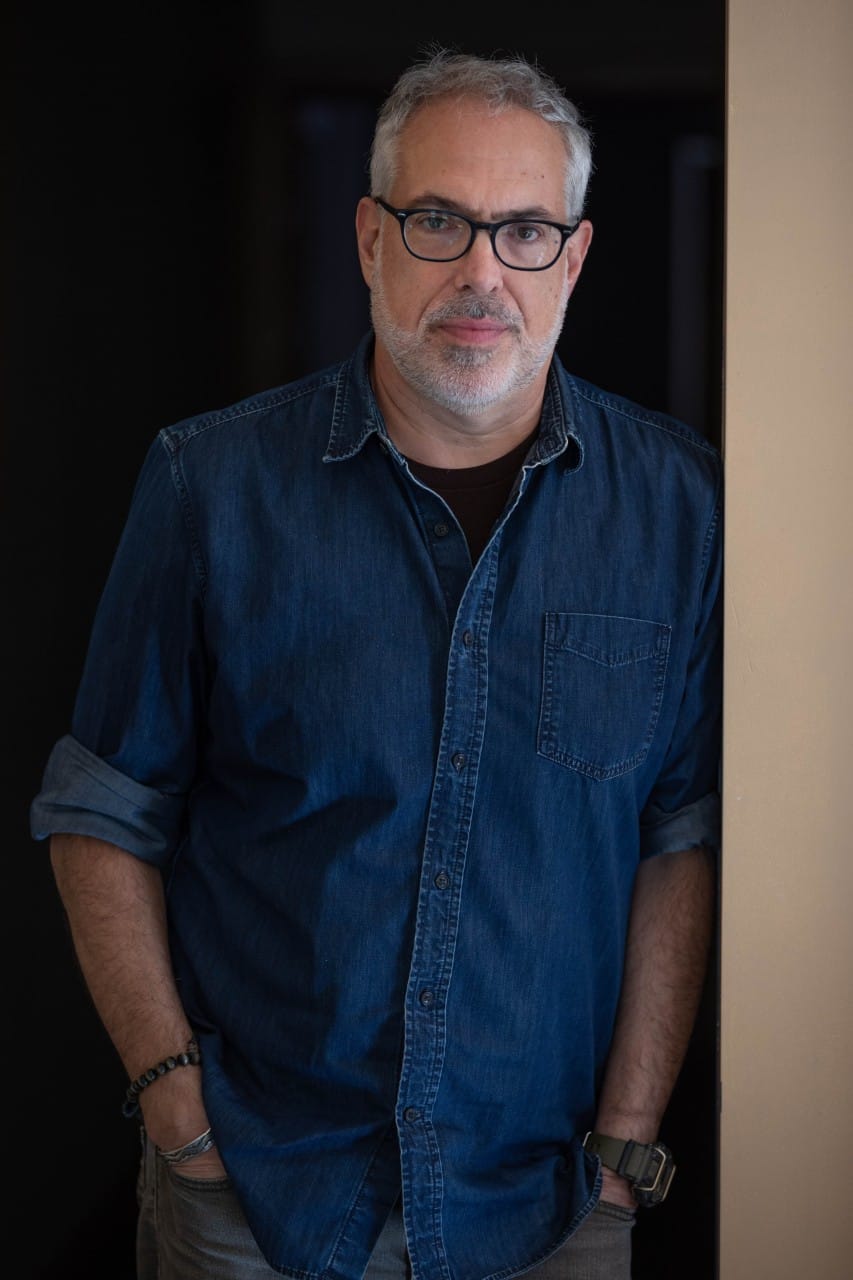

Born to Make Music — Alumni Profile, Jacob Ribicoff ’86

Sometimes you have to give up a dream to find a new one — just ask Jacob Ribicoff ’86, the man behind the sound of “Severance.”

Emmy Award-winning sound designer Jacob Ribicoff ’86 has always been an ambitious storyteller. At Amherst, he hosted a four-hour-long radio show called “The Night Train.”

“I would spend hours digging through the station’s incredible vinyl collection,” Ribicoff said. “I basically traced the entire history of jazz — Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, bebop, free jazz, fusion — just educating myself. It was such a big part of my life at the time.”

While Ribicoff rode “The Night Train,” Jackie McLean, a Blue Note Records artist and one of Ribicoff’s all-time favorite alto players, was teaching at the Hartt School of Music nearby in Hartford.

“I called him up — I’d never interviewed anyone before,” Ribicoff chuckled. “But he just said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ve done a million interviews. If you don’t know what to ask, I’ll tell you what to ask me.’”

Ecstatic, Ribicoff lugged his boombox and a fresh cassette tape to West Hartford, and before long, he was sitting beside a world-class jazz musician, firing away.

“It was my first time editing anything like that,” he said. “I cut up the interview, then played some of McLean’s music in between. It made for a real special broadcast.”

All The Things You Are

Today, 40 years removed from that “special broadcast,” Ribicoff has worked as a sound designer on over a hundred projects, including “The Darjeeling Limited,” “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” “Manchester by the Sea,” “Fahrenheit 451,” “Passing,” “Past Lives,” and “Baby Girl.” He’s the lead sound editor of the 10-time Emmy-winning show “Severance” and has a long-time filmmaking collaboration with Hampshire College graduate and documentarist Ken Burns, working on, among others, “The War,” “The Vietnam War,” and the upcoming six-part documentary series “The American Revolution.”

In other words, in a vast sea of filmmaking professionals, Ribicoff is one big fish — a whale shark or a majestic blue marlin. And, oh, he’s a father, a husband, a musician, a proud New York City native, and a humble Amherst College graduate.

I spoke with him for about two hours on a cool, rainy evening in early October, and if my experience is any indication, Ribicoff — honest, vulnerable, and introspective — is a heck of a lot more than his resume.

Free For All

“How is your semester going?” Ribicoff asked me.

“Really, really busy,” I said.

He laughed: “It hasn’t changed.”

Ribicoff arrived at Amherst in 1981 from the notoriously difficult Stuyvesant High School in New York City. Despite this, he struggled academically.

“It was like … I don’t know how it is now, but back then, the philosophy was to assign 10 books at a time, and each one would be, you know, 500 pages long,” Ribicoff said. “It was overwhelming.”

Still, motivated by a deep-seated love for storytelling, Ribicoff became an English major.

“There were definitely things I was really interested in at Amherst,” he said. “I thought maybe I’d write screenplays — that was something I imagined myself doing back then, but it never really worked out.”

Ribicoff did not find himself through the open curriculum. Instead, his most rewarding experiences came from outside the classroom. He poured his energy into Amherst’s creative communities, finding his voice through WAMH, acting on stage, and playing music with friends. While hosting “The Night Train” became his laboratory for musical discovery, spontaneous saxophone performances gave him a taste of the creative process.

“I remember playing a totally freeform saxophone improvisation during Black Student Weekend in the Octagon — just channeling whatever came through me,” Ribicoff said. “It was incredible. I felt transported, not at all self-conscious.”

Sweet Love of Mine

These days, when Ribicoff is at his busiest, he might find himself juggling as many as four major projects at once. His work on any one project can take anywhere from a week to over a year. Episodic shows normally take the longest — with Season Two of “Severance” requiring about a year and a half of work — while most feature films take about five months, and most documentaries (non-Ken Burns documentaries, of course) take only about a month.

Each project comes with its own goals, idiosyncrasies, and challenges, but more often than not, Ribicoff’s “hyperreal” approach remains the same.

“If you just recorded what was really there, it would be underwhelming,” he said. “You have to enhance things if you want them to feel dramatic — or violent, or anxious, or queasy, or whatever the moment calls for.”

Take, for instance, Ribicoff’s work on Darren Aronofsky’s 2008 film, “The Wrestler,” which chronicles the fictional comeback of an aging wrestler named Randy “The Ram” Robinson.

To truly capture this world, the sound design must not only reflect what’s visible on screen, but also amplify the swirling boundary between authenticity and heightened spectacle — a dividing line pro wrestlers call “kayfabe.”

Ribicoff and his colleagues started by field recording at a real wrestling school in Allentown, Pennsylvania, capturing the visceral details as clearly as they could:

“We’d put the microphone as close to the point of impact as possible — feet or bodies hitting the mat, skin on skin,” Ribicoff said. “We even placed a mic underneath the ring to catch the noise from this huge coil designed to make things super noisy.”

In post-production, Ribicoff and his team continued their hyperreal work, pushing the drama even further. He takes particular pride in how seamlessly they mixed the raw authenticity of their fieldwork with heightened effects.

“We added elements that were much larger than life — big metal impacts, lots of low-end, sometimes a sweetener under the mat hit — just to make it that much more viscerally violent,” he said. “There’s some unreal stuff in there that you wouldn’t even know to listen for.”

For Ribicoff, “The Wrestler” stands out as one of his finest achievements — a perfect example of how hyperrealism can elevate a film.

Around the same time, Ribicoff also began work on Wes Anderson’s 2009 animated film “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” based on the Roald Dahl book of the same name. As he often does, the enigmatic director took an unusual approach to the production process.

“He likes to do everything unconventionally,” Ribicoff said. “Normally you’d start with animatics — those moving storyboard sketches — but he said, ‘No, I don’t want to do it that way.’ There wasn’t a single drawing, just the script.”

For three days in September 2007, the cast and crew traveled to a farm in rural Connecticut, where they filmed each scene before later turning it into animation.

“We brought George Clooney and had him along with Bill Murray and a couple other cast members just read straight from the script,” Ribicoff chuckled. “If the scene called for a stream, we’d actually go to a stream on the farm and record the dialogue there.”

Unlike “The Wrestler,” though, hardly any of their fieldwork actually made it into the film.

“It was a nightmare later, trying to make those real, outdoor recordings work with animation,” Ribicoff said. “In the end, most of it had to be redone in the studio — but Anderson’s approach, I think, really set the tone for [the production process] that followed.”

Giant Steps

In a film class taught by Professor of English John Cameron roughly 20 years earlier, Ribicoff began reading movie credits all the way to the end.

“I remember thinking, wow, there’s something called a sound editor. That’s an actual job. A mixer — that’s a career. That’s something people get paid for? I had no idea,” he explained.

Ribicoff filed this away, and a few years later, he acted on it, eventually securing a job as a sound engineer for the “Wizard of Sound” Tony Schwartz in New York City.

While working for Schwartz during the weekdays, he began attending a vocational school for audio at night and working on student films over the weekend, fully immersing himself in the art of sound.

“Sometimes, I’d just sit in the park with a pad, jotting down every sound I noticed,” he said. “I’d note the distant traffic, a horn here, a siren there, birds and kids on the playground, honestly, I’d just try to map where each sound came from, observing how it all layered together.”

Not long after, Ribicoff secured his first union job recording car sounds in Brooklyn for the 1995 film, “New Jersey Drive,” and from there, he never looked back.

Now’s the Time

Just this last September, Ribicoff won his second-ever Emmy award for his mixing work on the earth-shatteringly successful Apple TV show, “Severance.”

“It’s just so unique,” Ribicoff said. “It’s not like anything you’ve seen before — it really has its own voice, and I’m proud to be part of it.”

The show follows Mark Scout (Adam Scott), an office worker whose memories have been surgically divided between his work and personal lives. This unsettling premise, accompanied by the show’s labyrinthine hallways, cold lighting, and surreal tone, demands a soundscape that blurs the line between reality and nightmare.

Ribicoff views the entire show as a dream, with specific episodes achieving a “heightened dream” state. Because of this, he approaches each scene with a surrealist mindset, aiming to create an uncanny soundscape that conveys the unsettling, enthralling world of Lumen and Kier.

“With sound design, you have to feel transported yourself before you can bring others along on that ride,” he said. “That’s really the point of entertainment: to offer people an escape from their everyday lives, even if just for a moment.”

“Severance” is one big mystery, like “Lost” or “Twin Peaks.” The writers leave clues, the directors stage them, and the dedicated fanbase tries to piece them together.

This past season, fans began theorizing about the significance of even the smallest sounds — particularly a few mysterious elevator “dings” that were off-pitch or entirely absent. These tiny differences spawned Reddit threads, TikTok clips, and YouTube videos, with many dedicated viewers believing that each tone, absence, or subtle variation was a clue carefully seeded by the creators.

Ribicoff, for his part, finds the theories both flattering and a little surreal. The reality behind these decisions, he explains, is rooted less in secret symbolism and more in musical craftsmanship.

“I would pitch the dings to sit well with the music,” he told me. “So with the score, the ding wouldn’t clash or be dissonant, you know? It has to have a rhythm that works with the soundscape and is very musical.”

As for the occasional absence of a ding, Ribicoff has a simple explanation: If a ding is missing, it’s probably because something in the music, or the dialogue, or even the editing made the sound too obtrusive. Sometimes, he told me, leaving it out just worked better for the scene.

“Having every sound decision picked apart by the audience — that’s not something I’ve really dealt with before, at least not until ‘Severance,’” he said. “We’ll see, I might really feel that hyper-awareness during Season Three, now that people are watching and listening so closely.”

Round Midnight

Saying “yes” to nearly every opportunity is a crucial part of making it as a creative professional. This is particularly true if you are a freelancer — be it a musician, a writer, or an artist — and is exactly how Ribicoff has operated throughout his long career.

“Back in the day, I’d walk around the city with my resume, popping into every cutting room and saying, ‘Hey, I’m available — hire me!’” he said. “I put myself out there and hoped the right door would open.”

Things “got their craziest” after the pandemic eased up, and Ribicoff was routinely working on as many as four jobs at once.

“It’s not something I recommend,” he said. “It’s neither sustainable nor healthy — but some of these projects, especially when they came from repeat clients, were hard to turn down.”

Nowadays, though, fresh off an Emmy win and at the height of his powers, Ribicoff's perspective is beginning to change.

“For a very long time, ‘no’ really wasn’t in my vocabulary, but I think it’s finally starting to creep in, and we’ll see if that lasts,” he said.

Along Came Betty

Make no mistake, Ribicoff’s journey has been far from linear. At Amherst, a young Ribicoff’s passion for the saxophone ballooned while learning under jazz musician Marion Brown, who had previously played with John Coltrane. He was so sure it was his calling, in fact, that he almost dropped out of college to pursue music.

“I was struggling with my grades, and my parents told me, ‘You need to put the saxophone away and make sure you pass your classes.’ There’s part of me that wishes I’d just said, ‘Forget it— I’m playing the saxophone no matter what.’ But, in the end, I stayed and graduated.”

Despite this, though, immediately after graduating, Ribicoff attempted to “make it” in New York City. His passion for music had always been a powerful force in his life, and now, he was going for it.

“Back in high school, I’d cut class at Stuyvesant and go play saxophone in the park. Whenever I played — especially with others — I’d get into this ecstatic, almost out-of-body state, like I was somewhere else entirely,” Ribicoff said. “That’s what I love about music: You can leave yourself behind and bring others along for the ride.”

For two years, Ribicoff played as much as he could. He practiced the saxophone for five hours a day, played in sprawling late-night jam sessions, and supported himself by waiting tables at One Fish, Two Fish on the Upper East Side. And yet, no matter how hard he tried, it just wasn’t happening.

Unsure of what he should do next, he did something distinctly Ribicoffian: He called Jackie McLean for advice.

“Man, what are you doing trying to play the saxophone?” McLean told him. That’s not what you do! That’s not what you do! You’re meant to do something else!”

And so — Ribicoff put down his saxophone — changed directions — and thus began his illustrious audio career.

Comments ()